(This article originally appeared in Get Ahead Magazine, for the Get Ahead Festival of independent short films in Brooklyn.)

When we speak of the identity of a place, we express a recognition of the patterns formed around us. We may not be conscious of them to the point of being able to draw them back with precision like Stephen Wiltshire, but we can remember them in the abstract, and in this way, identify different places from the abstractions we recall of their patterns. This is how one street can look sufficiently alike another that we can identify a neighborhood, and it is also why a landscape like Liberty City in Grand Theft Auto can feel like New York City, despite the fact that every object has been reconfigured to create a parody environment.

A city’s identity is made by the patterns selected by the people who built them. We can also say that these patterns are the fossil record of the people who inhabited a place. We can read the history, the culture and the sustainability of a place by the combination of its patterns. A building is a hierarchical computation of different processes nested within each other, and these processes can be substituted for others depending on what conditions are encountered.

At the largest scale of patterns there is the building program, whether a house, a church, an office, easily recognizable in any cultural setting. These programs are realized using construction techniques that are conditioned on economic constraints. The Dutch who settled New York City brought with them their basic house program, but these had to adapt to the resources available by, for example, building in brownstone, an economic pattern. Despite this difference they kept features of their homes like stoops, patterns that were at first environmental but then became cultural.

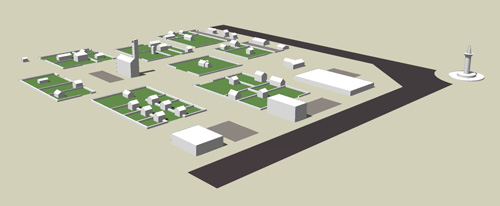

As each successive culture either migrates to or emerges in the city, it needs to adapt the patterns of its buildings to fit its own practices. Fractals like these become habitual:

This is Chinatown in Brooklyn. We can tell it is Brooklyn because the basic patterns, program and materials, are Americanized Dutch. We can tell it is Chinatown because of the use of vertical commercial signs which are characteristic of oriental cultures (their writing being read top-to-bottom instead of left-to-right). The large-scale patterns are extended by smaller-scale patterns to form a full building fractal that is Dutch, American, New York and Chinese. This combination of pattern is the identity of Brooklyn, the people who have lived there and continue to live there.

One particular culture that has often been denounced as an anti-culture is the global corporation. Their aesthetic program has been to impose their corporate identity uniformly on communities, regardless of any consideration for local economic, environmental, or cultural factors. But there have been exceptions, such as the following case, where the corporation decided to extend the patterns of the neighborhood instead of imposing its own.

This Dunkin’ Donuts nested itself seamlessly in an old Dutch building next to a Chinese restaurant, and even improved upon it a bit with orange awnings that preserve the structure of the windows while announcing the presence of this corporate neighbor to everyone on the street. As well as being a demonstration of Dunkin’s neighborliness, it is also a demonstration of the sustainability of the neighborhood. The buildings are resilient, and despite the Dutch builders never anticipating that there could ever exist such a thing as a Dunkin’ Donuts, their patterns have been slightly adapted to fit today’s needs. Some day Dunkin’ Donuts will also be history. In its place will be some other culture which may or may not preserve traces of Dunkin’s presence, but the building itself will remain and serve a new purpose.

So far I haven’t said a word about architecture, which is simply because architecture does not enter the picture unless one has a lot of money for sculptural elements. It is possible to build a good neighborhood without architects, but a great one needs art, and that means getting some architects involved. The best architecture starts with utilitarian patterns, the same functional, economic and cultural patterns we see above, and then expands it by nesting sculptural elements, thus it is still possible to recognize identity of place behind the architecture. This architecture, sculpting the utilitarian shape of the building, becomes the final expression of identity, the artistic currents and fashions that propagate across cultures and then vanish, only to make periodic comebacks.

This is what Brooklyn architects did with these residential towers overlooking prospect park. What is in essence a stack of identical apartments made with the usual economic patterns was extended with sculptural ornament, most impressively around the otherwise obnoxious elevator shafts.

Looking at Brooklyn’s tallest landmark, the Williamsburg Savings Bank Tower, we see patterns that are Gothic, Romanesque, Italian renaissance, Art Deco, all nested within each other and wrapped around a stack of floors that can fulfill any purpose whatsoever. The final product is a building that is worth preserving from a bank, to dentist’s offices, to residences, because the patterns cooperate with each other instead of clashing, and answer our need to feel connected to any of these identities. This is another form of sustainability.

The tragedy of architecture in the 20th century, and the great confusion that came from it, is that modernist architects first banned sculptural elements in favor of purely standardized, globally uniform, utilitarian industrial patterns, then post-modernist architects declared that a building was only a sculpture for living, that the utilitarian should be subordinated to the architect’s artistic expression. The outcome has been a building culture that has no identity when it is not completely incomprehensible, and more than likely has no resilience and no future.

This “Dance Center” is a sad example of this confusion. Were it not spelled out in letters, would we be able to understand anything about this building’s identity? The people who occupy it? What any of its parts do, or if they do nothing at all and are simply there for visual effect? I can’t imagine a future for it. But there is worse.

This building makes no attempt at being anything other than mass human storage, the modernist tower block revived for the bubble epoch. It will likely be a financial failure for being too ambitious while being too redundant. If I were to take an apartment there, it would be impossible for me to tell which window is mine from the outside. What does this say about the people who built it? That they took the easiest path to financial income. What does this say about the people who will live there? That they have nowhere else to go. It is and will remain an alien in the neighborhood, a product that removes identity instead of contributing to it.

Today’s planning establishment attempts to reform the shape of our cities with “form-based codes” that dictate with precision the shape of every pattern. This comes at the cost of outlawing certain unforeseeable patterns that may make a net contribution to the identity of place. It also drives away people that need these patterns, and drains life that is needed to renew the neighborhoods. Last of all, it will not stop a monster like the example above. If instead of dictating shapes, we made it clear how to expand and preserve the neighborhood’s identity, we would all be much freer to live and express ourselves, adding to the history of our environment.