This is part I of a series of excerpts of an article to be published in the International Journal of Architectural Research entitled The Principles of Emergent Urbanism. Additional parts will be posted on this blog with the editor’s permission until the complete article appears exclusively in the journal’s upcoming issue.

Of the different domains of design urban design is an oddity. While the design of a machine can be traced to a definite, deliberate act of invention, and even the design of buildings (architecture) is rooted in known production processes, the design of cities was never seriously attempted until well after cities had become a normal, ordinary aspect of civilized living, and while the design of machines and buildings was a conscious effort to solve a particular problem or set of problems, cities appeared in the landscape spontaneously and without conscious effort. This places the efficacy of urban design in doubt. The designers of machines and buildings know fully how the processes that realize their design operate, and this knowledge allows them to predictably conceive the form they are designing. Urban designers do not enjoy such a certainty.

How is it possible for what is obviously a human artifact to arise as if by an act of nature? The theory of a spontaneous order provides an explanation. According to Friedrich A. von Hayek (Hayek, 1973) a spontaneous order arises when multiple actors spontaneously adopt a set of actions that provides them with a competitive advantage, and this behavior creates a pattern that is self-sustaining, attracting more actors and growing the pattern. This takes place without any of the actors being conscious of the creation of this pattern at an individual level. The spontaneous order is a by-product of individuals acting in pursuit of some other end.

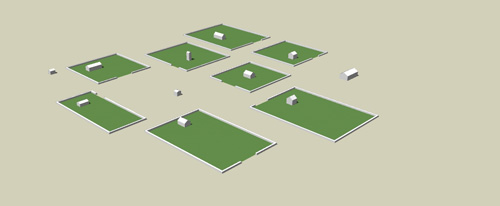

In this way cities appear as agglomerations of individually initiated buildings along natural paths of movement, which originally do not require any act of production as dirt paths suffice. As the construction of individual buildings continues the most intensely used natural paths of movement acquire an importance that makes them unbuildable and these paths eventually form the familiar “organic” pattern of streets seen in medieval cities. This process still takes place today in areas where government is weak or dysfunctional, notably in Africa where urban planning often consists of catching up to spontaneous settlement, and in the infamous squatter slums that have proliferated in the 20th century.

A transect of the city of Tultepec in Mexico provides a snapshot of the different phases of spontaneous urban growth. (Google Earth image)

As urbanization becomes denser, the increasing proximity of concurrent, competing individual interests causes conflicts between the inhabitants of the emerging town. Individuals build out their properties in such a way that it interferes with others, for example by blocking paths or views. These acts threaten the sustainability of the spontaneous order, and to resolve this situation the parties involved appeal to the same judges that rule on matters of justice. These judges, again according to Hayek, are required to restore and preserve the spontaneous order with their rulings. These rulings provide the first building regulations and, when government authority becomes powerful enough to do so, are compiled into comprehensive building codes to be applied wherever the force of that government extends. (Hakim, 2001)

The compiled building codes are later brought by colonists to create new settlements, reproducing the morphology across multiple towns but each time in a pattern that is adapted to the local context. Early town planning efforts are attempts at regularizing the building codes in order to plan for long-term organization of cities, but maintain the spontaneous production process. Most notably the rapid urbanization of New York City was accomplished by very simple rules on the size of blocks laid out in the 1811 Commissioners Plan for New York. Unlike the experience of urbanization in previous centuries, where urban growth was slow and often stagnant, the urbanization of New York took place in a time of rapid social and economic changes, and the city government had to invent building codes involving issues that never could arise in a pre-capitalist society: first the tenement, then the skyscraper, and ultimately, the automobile.

Modernism: the replacement for the spontaneous order

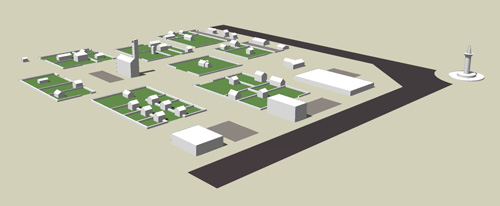

Architects and urban planners of the early 20th century, confident in the techniques of engineering and industrial production, believed that the spontaneous city had become irrational and had to be replaced with a new design fully integrating new industrial technology. The Swiss architect Le Corbusier is famous for designing a complete city around the automobile and building models of his design. In so doing he adopted a process of urbanization that was completely planned hierarchically, applying the processes familiar to architects at the scale of an entire city. He also ridiculed the morphology of spontaneous cities as being the product of donkey-paths.

This scale model of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin marks the turning point where city plans as constraints on individual initiative are replaced with architectural design at the scale of millions of inhabitants. (Le Corbusier, 1964)

Although the architectural program of high-rise living of Le Corbusier was discovered to be a colossal failure, the modernist process of development replaced spontaneous urbanization in the industrialized world. The housing subdivision substituted adequately for the high-rise tower block, providing affordable housing in large numbers to a war-impoverished society. This production process is still in force today, separating cities into three distinct zones: residential subdivisions, industrial and office parks, and commercial strips.

Modern city planning has been successful at its stated objective, producing a city designed specifically around automobile use, yet it was immediately and has been perpetually the target of criticisms. Most significantly the vocabulary of these criticisms had to be invented in order to spell out the critics’ thoughts because the type of deficiency they were observing had never been seen. Words like placeless or cookie-cutter were invoked but fell on the deaf ears of urban planners who were trained in Cartesian processes and industrial production techniques.

The most devastating criticism of modernist urban planning came in the form of a sociological study and personal defense of the spontaneous city, the book Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs. (Jacobs, 1961) In it she described in great details how the functions of a spontaneous city related and supported each other. Her concluding chapter, the kind of problem a city is, is still the most relevant. In it she attacks the scientific foundations of urban planning at a paradigmatic level, and claims that the methodology of the life sciences, at the time undergoing the revolution created by the discovery of DNA, is the correct approach to studying cities.

Death and Life of Great American Cities has been adopted by contemporary urban planners as a textbook for urbanity. Its descriptions of the characteristics of a city are now the models upon which new developments are planned. The old urban development of housing subdivisions and office parks is being substituted for the new urban development that has streets, blocks, and mixed uses, just as Jacobs had described to be characteristic of life in the city. A major difference between Jane Jacobs’ preferred city and the new urban plans remains. The layout of mixed uses is organized and planned in the same process as Le Corbusier planned his city designs. The scientific suggestions of Jacobs have been ignored.

The discovery of emergence and complexity science

In the time since Jacobs published her attack on planning science molecular biology has made great technological achievements and provided countless insights into the morphology of life. In parallel the computer revolution has transformed the technology of every human activity, including that of design. But the computer revolution brought along some paradigm-altering discoveries along with its powerful technology. In geometry, the sudden abundance of computing power made it possible for Benoit Mandelbrot to investigate recursive functions and his discovery, fractal geometry, generated a universe of patterns that occurred in many aspects of the physical universe as well as living organisms. (Mandelbrot, 1986)

Some thinkers saw that the life sciences were part of a much more general scientific domain. They formed the Santa Fe Institute and under the label complexity studied not only organisms but also groups of organisms, weather systems, abstract computational systems and social systems. This research formed a body of theory called complexity science that has resulted in the creation of similar research institutes in many other places, including some centers dedicated specifically to urban complexity.

Their scientific revolution culminated in two major treatises within the last decade, both from physicists practicing in a field of complexity. The first was A New Kind of Science by computer scientist and mathematician Stephen Wolfram (Wolfram, 2002), where he presents an alternative scientific method necessary to explore the type of processes that traditional science has failed to explain, presenting a theory of the universe as a computational rule system instead of a mathematical system. The second was The Nature of Order (Alexander, 2004) by architect Christopher Alexander, where he presents a theory of morphogenesis for both natural physical phenomena and human productions.

A definition of emergence

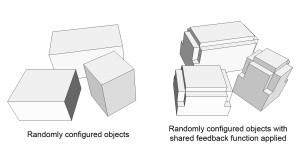

To define what is meant by emergence we will use the abstract computational system upon which Wolfram bases his theories, the cellular automaton. Each cell in a row is an actor, making a decision on its next action based on its state and the states of its direct neighbors (its context). All cells share the same rule set to determine how to do this, that is to say all cells will act the same way with the same context. In this way each row is the product of the actions of the cells in a previous row, forming a feedback loop. The patterns of these rows are not in themselves interesting, but when collected in a sequence and displayed as a two-dimensional matrix, they develop complex structures in this dimension.

The 30th rule of all possible rules of one-dimensional cellular automata produces a chaotic fractal when displayed as a two-dimensional matrix, but most other rules do not create complex two-dimensional structures. The first line of the matrix is a single cell that multiplies into three cells in the second line in accordance with the transformation rules pictured below the matrix. This process is reiterated for the change from the second to the third line, and so on. All the information necessary to create structures of this complexity is contained within the rules and the matrix-generating process. (Wolfram, 2002)

The same general principle underlies all other emergent processes. In a biological organism a single cell multiplies into exponentially greater number of cells that share the same DNA rules. These cells create structures in a higher dimension, tissues and organs, which form the entire organism. In the insect world complex nests such as termite colonies emerge from the instinctual behavior of individual termites. And in urbanization, buildings form into shopping streets, industrial quarters and residential neighborhoods, themselves overlapping into a single whole system, the city.

References

Alexander, Christopher (2004). ‘The Process of Creating Life’, The Nature of Order Vol. 2, Center for Environmental Structure

Corbusier, Le (1964). La Ville Radieuse. Éléments d’une doctrine d’urbanisme pour l’équipement de la civilisation machiniste, Édition Vincent Fréal et Cie, Paris, France

Hakim, Besim (2001). ‘Julian of Ascalon’s Treatise of Construction and Design Rules from Sixth-Century Palestine,’ Journal of the Society of Architectural Historian, vol. 60 no. 1

Hayek, Friedrich A. (1973). ‘Rules and Order’, Law, Legislation and Liberty Vol. 1, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London and Henley, UK

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House and Vintage Books, New York, USA

Mandelbrot, Benoit (1986). The Fractal Geometry of Nature, W.H. Freeman, New York, USA

Wolfram, Stephen (2002). A New Kind of Science, Wolfram Media, USA

It is with these concerns in mind that I set out to design the Emergent Urbanism Network, a pioneering social media portal that aims to deliver to you the knowledge you need to advance your own personal growth as well as contribute to the growth of your peers. It is a portal that you create and you structure, in combination with every other member, into a publication that is infinitely scalable. It is an emergent form of media advocating for an emergent city.

It is with these concerns in mind that I set out to design the Emergent Urbanism Network, a pioneering social media portal that aims to deliver to you the knowledge you need to advance your own personal growth as well as contribute to the growth of your peers. It is a portal that you create and you structure, in combination with every other member, into a publication that is infinitely scalable. It is an emergent form of media advocating for an emergent city.

Emergent Urbanism at the University of Montreal

I was invited to the complex systems laboratory of the Université de Montréal this week to present emergent urbanism to their twenty-member large research group. Click through to SlideShare in order to see the full text of the presentation under the “notes on” tab. The entire text is in French, however I know a significant share of this website’s visitors enjoy French once in a while.

If someone wants to sponsor me for a translation in English, email me and I’ll upload one very soon. Otherwise my hands are quite full at the moment, it might be a while before I get around to it.

Thanks to Rodolphe Gonzales from the Complex Systems Lab for the invitation. You can read about their work here.

1 Comment

Posted in Commentary

Tagged Bill Hillier, christopher alexander, complexity, emergence, Michael Batty, Nikos Salingaros, Pierre Frankhauser, Planning process, slides, Space Syntax, Stephen Wolfram, University of Montreal